Grammar

- Defending The Queen's English

What is it about American phrases and spellings that some Britons find so offensive? Extremists (loyalists even?) might refer to British English as “The Queen’s English”. You lazy Americans are distorting the language and thereby insulting the Queen....

- Try And ... Get Over It

In informal English, we often use idiomatic expressions with and instead of the infinitive marker to, when linking certain verbs with a following infinitive: Come over here and look at these lovely flowers. I'll just go and get something to...

- Confusing Words - Matching Exercises Based On Two Top Ten Lists

Among the growing number of 'Top 10 lists' at Merriam-Webster online dictionary are two sets on confusing words. Here are a couple of exercises based on them. Merriam-Webster Top 10 confusing words - Set 1 Try the exercise without...

- The Which-hunting Season Is Upon Us Again.

A minor spat about the use of which and that in relative clauses Which-hunting, a play on words on witch-hunting (see link below), is a term used by linguists to refer to the criticism by some of the use of which for things, in defining (aka restrictive...

- More Goodies From Merriam-webster

As well as being a dictionary, Merriam-Webster Online has several resources that could be useful to advanced learners, including a new Top Ten Words Easily confused words These are the subject of Merriam-Webster's latest Top Ten Words, which...

Grammar

A British perspective on further or farther

The question of further vs farther is a popular topic on grammar websites and has been discussed often enough on sites like GrammarGirl, so why should it need anything more said about it?

Because firstly, nearly all these websites are American, and the British 'take' on this question is somewhat different. And secondly, they nearly all put forward a so-called 'rule' which is by no means universally accepted.

Two meanings

We use far in two ways: to talk about distance, and to talk about how much

- Do you live far from your work?

- This coffee is far better than that one.

Similarly we use the comparative further / farther to talk about distance, and also to talk about amount or degree. In this use it is often synonymous with more.

Exercise - If you think further / farther in these sentences is about distance, click on 'Yes'. If you think it's about amount, quantity or degree, click on 'No'.

| Yes | No | |||

| 1. | How much farther is it to the station? | |||

| 2. | We will have to give this matter further attention. | |||

| 3. | David agrees with Peter, but goes even further than him. | |||

| 4. | Come on. It's not much further, and then we'll be home. | |||

| 5. | I don't want to talk about this any further. | |||

| 6. | The plan has been so successful, we want to take it even further. | |||

| 7. | Our new house is further from the school than the old one. | |||

| 8. | So without further ado, I would like to start the meeting. | |||

| 9. | Nothing could have been further from my mind. | |||

| 10. | It was farther than we thought, and we arrived rather late. | |||

| 11. | So that's decided then; no further discussion is necessary. | |||

| 12. | I got no further than the corner when I realised I'd left my umbrella. |

Discussion

The expression - further from my mind - is not admittedly about physical distance, but metaphorical distance. It doesn't refer to amount or more. But some people see it as a grey area which could be interpreted either way - distance or other.

The debate begins

Once upon a time, it would seem, there was only one comparative of far, and that was further. It was later joined by farther, and the use of the two words became 'more or less interchangeable', to quote Merriam-Webster.

But towards the end of the nineteenth century, the then editor of the Oxford English Dictionary (widely regarded on both sides of the Atlantic as the authority on the English language) decided that farther should be used to refer to distance, and further should be used to refer to quantity or degree.

In Britain, Fowler, at that time the most respected authority on English usage in Britain, disagreed. He said that that most people used either one or the other, independent of whether they were referring to distance or degree. And he went on to say that further was the more popular, and would even one day oust farther altogether.

Divergence of usage

What in fact happened was slightly different, and the two strands of the English language began to go their separate ways.

In the US especially, many commentators followed the advice of that OED editor, and it is now stated on many grammar websites (mainly American) that farther should be used for distance and further for 'more' etc.

In Britain, however, while generally agreeing about the use of further when talking about quantity, amount or degree, most British commentators see further as just as correct as farther when talking about distance. Swan, the standard usage guide for learners (BrE) says:

We use both farther and further to talk about distance. There is no difference in meaning. ... We can use further (but not farther) to mean 'additional', 'extra', 'more advanced'.

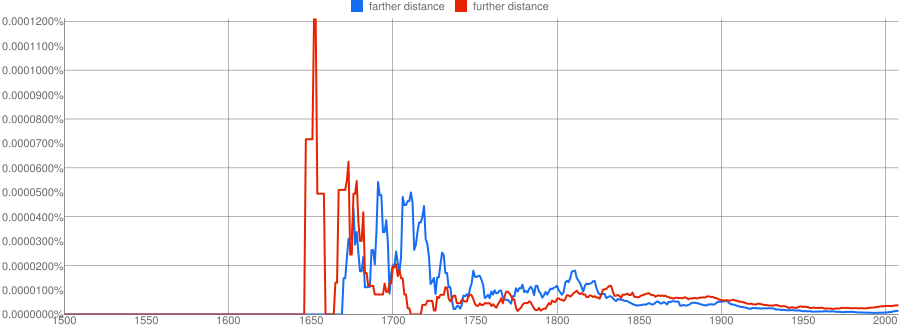

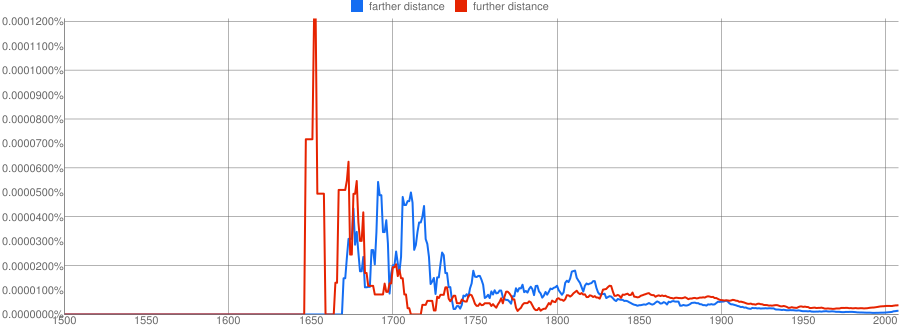

And what Fowler predicted indeed appears to be happening in Britain; further seems to be supplanting farther, as can be seen in this Ngram graph.

According to The New Fowler's (1996):

...in so far as the [farther] forms are used at all, they are now more likely to occur in AmE than in BrE, though the distinction is not clear-cut.

Linguist Terry Watt of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh has done a bit of research on this subject and notes (link below):

The ratios of farther to further are clearly in favor of further. Obviously Australia and the United Kingdom have no respect for American usage notes: they have almost eliminated farther altogether. It is especially interesting to note that the BBC corpus contains absolutely no cases of farther.

In fact, even in the United States, actual practice doesn't necessarily follow the dictates of the grammarians, and the use of further to talk about distance is common there as well. It's just that their traditional grammarians don't seem to recognise this fact.

My tip - forget farther

In British English at least, the safest thing is just to use further for everything and forget farther. Then you don't need to worry whether it's about distance, real or metaphorical, or something else. And in any case, it's what most of us native speakers do. The same goes for the superlative: furthest.

Etymological note

Some websites suggest that further comes from an old English word meaning to impel. This rather suggests that farther is the true comparative of far, and that further sort of got borrowed. There is indeed a verb to further, meaning to help something to develop or be successful (OALD) as in:

- He would do anything to further his career

- Violent demonstrations are not going to further our cause.

But the Online Etymology Dictionary, amongst others, suggests that the comparative further came from a different and older source: the words forth-er or fore-er. Forth and fore meaning roughly forward or away. This is confirmed by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary of English Usage and The New Fowler's. So don't let them try and tell you farther is the natural comparative of far. If anything, it's farther that is the 'usurper'!

One man's (or woman's) whim

This seems to be a good example of a situation where one person's opinion has been elevated into a grammatical 'rule'.

The same thing happened with less and fewer, where a certain Baker suggested in 1770 that fewer should be used for countable nouns and less reserved for uncountable nouns.

And singular they was quite respectable until one Anne Fisher (1719-78) decided that he and not they should be used when the gender wasn't known. Shame on her!

Links

- Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary - notes that further as a comparative of far (for distance) is used especially in British English.

- Merriam-Webster - look at the usage notes, but remember this is an American dictionary. Look in their entry on further and you'll see that their examples cover both uses.

- Daily Writing tips - generally sound - puts forward both sides of the argument, but although quoting Etymology Online, it's own etymology seems a bit shaky.

- HubPages - makes the standard American differentiation, but see what he says about Merriam-Webster

- GrammarGirl - talks about 'careful' writers making the distinction. But like with so many of these usage disputes, it's not that the the rest of us are 'careless'; we simply believe we have a choice.

- English Plus - makes the distance / amount differentiation without any discussion, as though it's a solid rule. Which it isn't.

- Online Etymology Dictionary - further (see also their entry for farther)

- Terry Watt - very detailed analysis, put in here only as a reference.

References

- Practical English Usage (Michael Swan - Oxford 1998) Amazon

- Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of English Usage (Merriam-Webster 1994) Amazon

- The New Fowler's Modern English Usage (ed. R.W.Burchfield - Oxford 1996) Amazon

loading...

- Defending The Queen's English

What is it about American phrases and spellings that some Britons find so offensive? Extremists (loyalists even?) might refer to British English as “The Queen’s English”. You lazy Americans are distorting the language and thereby insulting the Queen....

- Try And ... Get Over It

In informal English, we often use idiomatic expressions with and instead of the infinitive marker to, when linking certain verbs with a following infinitive: Come over here and look at these lovely flowers. I'll just go and get something to...

- Confusing Words - Matching Exercises Based On Two Top Ten Lists

Among the growing number of 'Top 10 lists' at Merriam-Webster online dictionary are two sets on confusing words. Here are a couple of exercises based on them. Merriam-Webster Top 10 confusing words - Set 1 Try the exercise without...

- The Which-hunting Season Is Upon Us Again.

A minor spat about the use of which and that in relative clauses Which-hunting, a play on words on witch-hunting (see link below), is a term used by linguists to refer to the criticism by some of the use of which for things, in defining (aka restrictive...

- More Goodies From Merriam-webster

As well as being a dictionary, Merriam-Webster Online has several resources that could be useful to advanced learners, including a new Top Ten Words Easily confused words These are the subject of Merriam-Webster's latest Top Ten Words, which...