Grammar

Whom watch #4 - On Messrs Gwynne, Lowth, Priestley and Shakespeare, with a few asides on the way

This is the fourth post in a series on the inappropriate teaching of the use of whom. In this post I look at:

- a silly grammar quiz question

- some early examples of who being used where the purists would demand whom

- conflicting views from the writers of two early grammar books

- how the whom camp triumphed for two centuries

- examples of object who in Shakespeare

and also take a few somewhat meandering detours on the way. Clicking on the framed extracts will usually take you to Google Books.

Mr Gwynne and his grammar quiz

Some time ago, The Telegraph newspaper ran what they called a 'Good grammar quiz', the first question being:

Which of these sentences is grammatically correct?

- Do you see who I see?

- Do you see whom I see?

Two things were immediately obvious: firstly, that the so-called 'correct' answer was going to be the 'whom' version, and secondly that nobody in their right mind would ever say this. Sure enough, the explanation given by Neville Gwynne, who had set the quiz, was:

"Who I see" should be “whom I see”. This is because “whom” is the object in the subsidiary clause “whom I see”, and must therefore be in the accusative or objective case.

Mr Gwynne's explanation is certainly in line with traditional grammar teaching, but unfortunately bears no relation to how English is actually spoken by the majority of its speakers. Mr Gwynne believes in prescriptive grammar, telling us what he thinks we should say, rather than descriptive grammar, which is based on how educated speakers actually speak. The grammar taught in EFL/ESL is largely descriptive.

The trouble with Mr Gwynne's answer is that it makes no allowance for register. Most people only use whom in formal English, not in everyday conversation. In 1908, Henry Fowler pointed out:

The interrogative

who is often used for

whom, as,

Who did you see? A distinction should here be made between conversation, written or spoken, and formal writing. Many educated people feel that in saying

It is I, Whom do you mean? instead of

It's me, Who do you mean? they will be talking like a book, and they justifiably prefer geniality to grammar. But in print, unless it is dialogue, the correct forms are advisable.

H.W.Fowler and F.G.Fowler - The King's English 1908

Mr Gwynne's example sentence is very much a conversational one. Imagine you are at a party, in the supermarket or in the street, and you see somebody you haven't seen for a while, or who(m) you didn't expect to see - you might well say - Look over there! Do you see who I see? But it's not the sort of thing you're likely to write in a formal text, except in dialogue.

Incidentally, 'Do you see who I see' gets 32 hits at Google Books (only one of which appears to be a grammar book). 'Do you see whom I see' gets a mere four, three of which are grammar books, and 'Do you see whom I' doesn't show up on [Ngram] at all.

Aside 1: who(m) do you mean?

Fowler mentioned the expression Who(m) do you mean? A search at Google Books for this expression in books between 1500 and 1799 brings up 21 for who and 33 for whom, with at least one classic author in each camp.

Henry Fielding - Amelia 1752

Daniel Defoe - Moll Flanders 1765

Even in books, who now appears to be in the lead. I wonder if we can put that red peak down to the influence of prescriptivism om 19th century English?

A little terminology

You'll have noticed how Mr Gwynne talks about the accusative or objective case. Grammarians have different ways of talking about the same thing, so this should make things a little clearer, before we look at some grammar books:

Nominative (case)

Subjective (case)

Subject form (EFL/ESL) | he, she etc | who |

Accusative (case)

Objective / Oblique (case)

Object form (EFL/ESL) | him, her etc | whom |

Objective who goes back at least to the sixteenth century

This use of who in object position is old as as the hills; there are over thirty examples of it in the works of Shakespeare alone (listed at the end of this post). It has even been said that constructions like this can be found as early as the fourteenth century (Merriam-Webster Dictionary of English Usage).

Here are a few from the sixteenth century:

Since the arrival of Clernau, the Queen is harder to do for any of those who she is offended with.

State papers Jan 29 1566 [Google Books] British History Online]

The firste parte of Churchyardes Chippes, Thomas Churchyard 1575

The honorable actions of that most famous and valiant Englishman, Edward Glenham Esquire 1591

Edmund Spenser - The Fairie Queene, Book 4 Canto 6 1590 (reproduced 1855)

The Geomancie of Maister Christopher Cattan, Christoforo Cattan, Sparry 1591

Seven English Poetical Miscellanies: Phoenix Nest, edited by John Payne Collier, 1593

Dr Lowth

One of the first to complain about objective who was R.M.Lowth (1710 - 1787), widely regarded as the first prescriptive grammarian. In his A short introduction to English grammar: with critical notes 1762, after presenting the rule about subject and object forms, Lowth wrote:

A short introduction to English grammar: with critical notes, by Robert Lowth, Cambridge 1838 (first published 1762)

In other words, Shakespeare and the philosopher John Locke had got it wrong.

Mr Priestley

Lowth's near contemporary, Joseph Priestley (1733-1804), took rather a different view. In later editions of his The Rudiments of English Grammar, originally published in 1761, he commented:

The Rudiments of English Grammar, Joseph Priestley, 3rd Ed. 1772

Aside 2: Mr Steele, Mr Addison, The Tatler and The Spectator

'Who should I meet the other day but my old friend'

Priestley uses this (shortened) quote from The Spectator to back his contention that good writers such as Richard Steele, used who with objective function. Ironically, in future grammar books it was more often used in error-correcting exercises than to show the acceptibilty of objective who.

Richard Steele (1672 – 1729) was at different times soldier, Whig politician and playwright / producer. In 1709 he founded The Tatler magazine with the intention of publishing coffee-house gossip; (a tatler is someone who gossips). Among the contributors were Joseph Addison, who Steele had been at school with, and Jonathan Swift, of Gulliver's Travels fame. Addison was an English essayist, poet, playwright, and politician.

The Tatler folded in 1711, and the same year Steele and Addison founded the Spectator. Although like Tatler before it, it only lasted a couple of years, its reputation is legendary, and bound volumes remained popular long after its demise, partly because: 'Its prose style, and its marriage of morality and advice with entertainment, were considered exemplary.' (Wikipedia)

Between The Tatler and The Spectator, we find this 'Who should I ... but ...' construction four times, three of them from Steele. What's more, neither magazine contain similar constructions with whom.

- ... who should I first encounter but my old friend Cynthio.

(Tatler - Steele)

- Who should I meet at the Coffee-house Door t'other Night, but my old Friend Mr. President?

(The Spectator Vol 1 No 32 Steele)

- A little after, as the Lady was discoursing my Friend, and held her Snuff-box in her Hand, who should I see in the Lid of it but the Doctor

(The Spectator Vol 1 No 57 Addison)

- ... but who should I see there but the most artful Procuress in the Town

(The Spectator Vol 2 No 266 Steele)

Some more examples of this construction are shown in Aside 8.

Lowth rules!

Unfortunately, it was Lowth's ideas that prevailed rather than Priestley's, and for the next two hundred years or so, the prescriptivists would dominate grammar writing. Steele's 'Who should I meet the other day but my old friend' became a standard sentence to be corrected in grammar exercises.

Perhaps the most famous prescriptivist grammarian to follow Lowth was Lindley Murray 1745 - 1826), whose English Grammar: Adapted to the Different Classes of Learners, first published in 1795, had enormous influence on both sides of the Atlantic. Murray has a strange theory about position:

English Grammar: Adapted to the Different Classes of Learners, Lindley Murray 1795 (this edition - New York 1809) [Archive.org]

Etymology and Syntax of the English Language, Alexander Crombie 1830 (3rd Edition)

Other grammars making use of Steele's quote include:

EXERCISES (sentences to be corrected)

The Principles of English Grammar: Comprising the Substance of the Most Approved English Grammars Extant, Peter Bullions, New York 1843

... correct these errors, giving your reasons in every instance

- Who servest thou under?

- Who should I meet the other day but my old friend?

- Who did he refer to, he or I?

- Who did he choose? Did he choose you and I?

- Who did you suppose it to be?

- Whom did you suppose it was?

Higher Lessons in English: A Work on English Grammar and Composition 1880 [Archive.org]

Correct all the errors in the following sentences:

- It is me.

- It was me who wrote the letter, and him who carried it to the post-office.

- I am sure it could not have been her.

- You would probably do the same thing if you were him.

- I understood it to be he.

- Whom do you think he is?

- Whom do men say that I am?

- Who do you think I saw yesterday?

- Who should I meet the other day but my old friend.

Practical English grammar, and business correspondence; for use in business colleges, normal and high schools, and advanced classes in the public schools 1888 [Archive.org]

Aside 3: It is I vs It's me

In that last example we saw how the sentences 'It is me.' and 'I am sure it could not have been her.' were considered incorrect. The verb be is technically followed by a subject form, not an object form, so purists would argue that the sentences should read 'It is I.' and 'I am sure it could not have been she.' But of course, as in the whom quiz example, few educated speakers actually talk like that.

We have already seen what Fowler had to say about this (in the extract about whom, above). And this was another area where Priestley found himself at odds with grammarians like Lowth:

The Rudiments of Grammar, Joseph Priestley, 3rd Ed. 1772

It's interesting how many of the contested areas of English are to do with pronouns. But it's perhaps not so surprising, as this is really the only area of English where we still have cases.

Finally, a bit of common sense

In An English Grammar, published in 1895, the authors W.M.Baskerville and J.M.Sewell write:

In spoken English, who is used as objective instead of whom; as, "Who did you see?" "Who did he speak to?"

And a bit later they say, giving several examples from the literary canon:

The interrogative pronoun who may be said to have no objective form in spoken English. We regularly say, "Who did you see?" or, "Who were they talking to?" etc. The more formal "To whom were they talking?" sounds stilted in conversation, and is usually avoided.

In literary English the objective form whom is preferred for objective use; as,—

- Knows he now to whom he lies under obligation? — Scott.

- What doth she look on? Whom doth she behold? — Wordsworth.

Yet the nominative form is found quite frequently to divide the work of the objective use; for example,—

- My son is going to be married to I don't know who. — Goldsmith.

- Who have we here? — Id.

- Who should I meet the other day but my old friend. — Steele.

- He hath given away half his fortune to the Lord knows who. — Kingsley.

- Who have we got here? — Smollett.

- Who should we find there but Eustache? — Marrvat.

- Who the devil is he talking to? — Sheridan.

Aside 4: Did Shakespeare really write 'Who do you speak to'?

Lowth includes this quote from As You Like It in his list of errors. But the Project Gutenberg version of the Complete Works didn't seem to include this lime, although a separate Project Gutenberg text of As You Like It did include it. In fact there appear to be two versions of this line. The earliest edition of As You Like It I could find at Google Books was published in 1709 by Jacob Tonson, and it includes these lines:

As You Like It first appeared in print in the First Folio edition of Shakespeare's works, published in 1623. And in the facsimile version of the First Folio at Archive.org, that last line is rather different:

[Archive.org]

Which makes rather more sense to me. Several sources suggest that the line was in fact changed by Nicholas Rowe (1674-1718), sometime-time poet laureate and the first editor of Shakespeare. Tonson had bought the copyright to Shakespeare's works and his 1709 edition (the first after the folios) was edited by Rowe, who modernised the punctuation and spelling to the practice of his day. This assertion is credited to Edmond Malone (1741 – 1812), a Shakespearean scholar and later editor of his works.

The Plays and Poems of William Shakspeare: With the Corrections and Illustrations of Various Commentators 1821

At least one editor obviously felt the same way as Lowth about the new version:

The Works: The Text Formed from an Entirely New Collation of the Old Editions, by John Payne Collier, Volume 3, London 1842

Not that it really matters; there are plenty of other examples of Shakespeare using who with an object function instead of whom.

Aside 5: The traditional rule: 'If it's him, it must be whom.'

The purists' rule is that if the answer to a question could be him, then the question should start with whom.

'Who does she love?' - She loves him - so it 'should' be 'Whom does she love'

But as we've seen, that rule bears no relationship to how the majority of educated speakers use English. But there is one situation when it can be useful, and that is to tell us when definitely NOT to use whom (at least according to the purist rules). People are so unused to using whom, and get told off so much for not using it, that sometimes they use it in what the purists would say is the wrong place.

Case 1 - So-called hypercorrection

Look at this sentence:

It might look as though the interrogative pronoun (who/whom) is referring to the object of say and so should theoretically be whom. But it is also the subject of called, and the need for called to have a subject is stronger than that of say to have an object. What's more, we couldn't answer it with 'him called', so for strict grammarians whom would be incorrect here.

The conventional wisdom is that people say this because they think it sounds more correct - hence 'hypercorrection'. This was the view held by Fowler, for example, who hated it. But others, for example Oto Jespersen, find whom natural and correct in these constructions. And of course, there are a few examples of this in Shakespeare (it appears you can prove anything with Shakespeare!), such as this one:

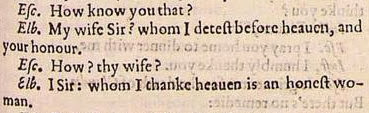

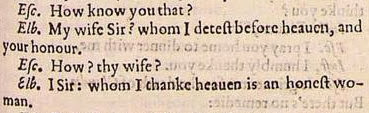

Measure for Measure, Act 2 Scene 1, from the 1623 First Folio [InternetShakespeare]

In this extract, the first instance of whom has the normal function of object (of detest), but in the second instance refers to the subject of is - she is an honest woman. The I thanke heaven part is parenthetical, and in some later editions appears between commas, as in this one, published in 1767 by J & R. Tonson.

Mr. William Shakespeare: His Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies, Volume 2, J & R. Tonson, London 1767

The change may well have been made by Nicholas Rowe, who(m) we met earlier, as his 1709 edition was also published by Tonson, who, incidentally, was the founder of the Kit-Kat Club, a London political and literary club whose members had included Joseph Addison and Sir Robert Walpole (generally regarded to have been Britain's first prime minister).

Case 2 - with finite be

Now look at this sentence:

Here we have a subject, it, and you are probably thinking the most natural answer is 'it was him' (which it of course is), so we should use 'whom'. But no, the purist will say, the verb be takes a subject form (a subject complement), so the answer should be 'it was he' and who is the correct form here.

So those are two cases where, according to purist grammarians, we definitely shouldn't use whom.

Case 3 - relating to an infinitive

But what happens when an infinitive is involved rather than a finite verb? Here are a couple of examples, the first one interrogative, the second one relative:

- Who did you ask to do it for you?

- It was Peter who I asked to do it for me.

To be honest, I wasn't sure whether the traditional rule would demand whom here, but it seems it does. As I read it, the answer to to the first one could be I asked him or I asked her (not he or she), so the purists would insist on whom. And in the second we could replace Peter with him (but not he), and so, again, the purists would say whom was required, even when the infinitive is to be.

Which might explain this strange pair of sentences I quoted earlier from Higher Lessons in English, where each sentence apparently has an error:

- Who did you suppose it to be?

- Whom did you suppose it was?

In the second sentence we have a finite form of be, as in Case 2 above, and so it technically takes a subject form - it was he and theoretically should be 'corrected' to who. As for the first sentence, my understanding is that as the infinitive doesn't take a subject, the answer to the first one is I supposed it to be him / her, so theoretically we 'should' use whom. .

This is confirmed by this extract from a grammar book written for businessman and published in 1920. At the time it was written, business correspondence was a lot more formal than today.

| Confusion of cases—Objectives: me, him, her, us, them, whom. These should never be used as the subject of a finite verb. |

| Wrong | Right |

| Who is this package for? | Whom is this package for? |

| Who did you suppose it to be. | Whom did you suppose it to be. |

| I supposed that it was her. | I supposed that it was she. |

| I supposed it to be she. | I supposed it to be her. |

The Business Man's English, Spoken and Written, by Wallace Edgar Bartholomew, Floyd Hurlbut 1920 [Archive.org]

It's perhaps not a bad idea to know the formal rules the purists put forward, even if we then choose to mostly ignore them.

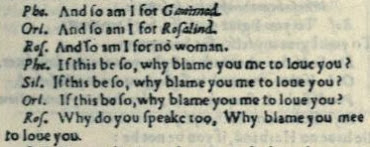

Mr Shakespeare's use of who instead of whom.

These examples of who being used with object function were found by checking all instances of who in the text of the Complete Works at Project Gutenberg, which is based on the 1623 First Folio editions. I've found thirty-five instances of who being used where strict grammarians would demand whom.

To put this into context, however, there are also about four hundred abd twenty instances of whom in the Complete Works. So it has to be admitted, that even for Shakespeare, whom was the norm. It was just that deviation from the norm doesn't seem to have been frowned on very much until Lowth came along.

- AGRIPPA. Who does he accuse?

Antony and Cleopatra, Act 3 Scene 6

- ORLANDO. Who doth he gallop withal?

ROSALIND. With a thief to the gallows;As You Like It, Act 3 Scene 2

- ADRIANA. May it please your Grace, Antipholus, my husband,

Who I made lord of me and all I had

Comedy of Errors, Act 5 Scene 1

- MENENIUS. Pray you, who does the wolf love?

Coriolanus, Act 2 Scene 1

- IMOGEN. His beastly mind to us, he hath a court

He little cares for, and a daughter who

He not respects at all.- What ho, Pisanio!

Cymbeline Act 1 Scene 6

- The heir of Cymbeline and Britain, who

The King his father call'd Guiderius- Jove!Cymbeline Act 3 Scene 3

- FRAN. O Lord, sir, who do you mean?

Henry IV Part 1, Act 2 Scene 4

- KING HENRY. Who serv'st thou under?

Henry V, Act 4 Scene 7

- Who join'st thou with but with a lordly nation

Henry VI Part 1, Act 3 Scene 3

- And care not who they sting in his revenge.

Henry VI Part 2, Act 3 Scene 2

- BASTARD. Who didst thou leave to tend his Majesty?

And bring some covering for this naked soul,

Who I'll entreat to lead me.King John, Act 5 Scene 6

- BOYET. Now, madam, summon up your dearest spirits.

Consider who the King your father sends,

To whom he sends, and what's his embassy

Love's Labour's Lost, Act 2 Scene 1

- To whom came he?- to the beggar.

What saw he?- the beggar.

Who

overcame he?- the beggar.Love's Labour's Lost, Act 4 Scene 1

- Whose loves I may not drop, but wail his fall

Who I myself struck down. And thence it is

That I to your assistance do make love,Macbeth, Act 3 Scene 1

- Were the graced person of our Banquo present,

Who may I rather challenge for unkindnessMacbeth, Act 3 Scene 4

- I may neither choose who I would nor refuse who I dislike;

The Merchant of Venice, Act 1 Scene 2

- whereof who chooses his meaning chooses you will no doubt never be chosen by any rightly but one who you shall rightly love

The Merchant of Venice, Act 1 Scene 2

- For who love I so much? And now who knows

The Merchant of Venice, Act 2 Scene 6

- GRATIANO. I have a wife who I protest I love;

The Merchant of Venice, Act 4 Scene 1

- The shallowest thick-skin of that barren sort,

Who Pyramus presented, in their sport

Midsummer Night's Dream, Act 3 Scene 2

- PEDRO. Who have you offended, masters, that you are thus bound to

your answer?

Much Ado About Nothing, Act 5 Scene 1

- IAGO. Not this hour, lieutenant; 'tis not yet ten o' the clock. Our

general cast us thus early for the love of his Desdemona; who let

us not therefore blame.

Othello, Act 2 Scene 3

- I lay unto the grievous charge of others.

Clarence, who I indeed have cast in darkness,Richard III, Act 1, Scene 3

- Dighton and Forrest, who I did suborn

To do this piece of ruthless butcheryRichard III, Act 4 Scene 3

- LUCIUS. Who should I swear by? Thou believest no god;

That granted, how canst thou believe an oath?

Titus Andronicus, Act V, Scene 1

- NESTOR. Why, 'tis most meet. Who may you else oppose

That can from Hector bring those honours off,

If not Achilles?

Troilus and Cressida, Act I, Scene 3

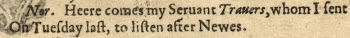

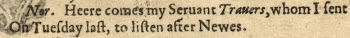

- PANDARUS. Who play they to?

SERVANT. To the hearers, sir.Troilus and Cressida, Act 3 Scene 1

- SERVANT. Who shall I command, sir?

Troilus and Cressida, Act 3 Scene 1

- HECTOR. Who must we answer?

AENEAS. The noble Menelaus.Troilus and Cressida, Act 4 Scene 5

- LAUNCE. Can nothing speak? Master, shall I strike?

PROTEUS. Who wouldst thou strike?

LAUNCE. Nothing.Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act 3 Scene 1

- He lives not now that knows me to be in love; yet I am

in love; but a team of horse shall not pluck that from me; nor

who 'tis I love; and yet 'tis a woman; Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act 3 Scene 1

- GAOLER. For a worthy lady,

And one who much I honour.

The Winter's Tale, Act 2 Scene 2

- I am put to sea

With her who here I cannot hold on shore.The Winter's Tale, Act 4 Scene 2

- This is a creature,

Would she begin a sect, might quench the zeal

Of all professors else, make proselytes

Of who she but bid follow.The Winter's Tale, Act 5 Scene 1

Aside 6: A little inconsistency, or perhaps a bit of tidying up?

On at least one occasion, who in an earlier edition has been changed to whom for the First Folio edition.

Henry IV Part 2, Act 1 Scene 1 Facsimile of 1600 First Quarto

Henry IV Part 2, Act 1 Scene 1 Facsimile of 1623 First Folio Internet Shakespeare

Aside 7: Idiosyncrasies of sixteenth century printing

While searching sixteenth century books (at Google Books) for instances of who being used instead of whom, I came across a lot of examples of something like whõ where you'd expect whom. It turns out that it was a custom taken over into printing from manuscript writing to represent the letters m and n after vowels by way of an accent over the vowel.

A godly and learned sermon, William Fulke 1580

The Countesse of Pembrokes Arcadia, Volume 2, Sir Philip Sidney, late 16th century

Aside 8: Who should I ... but ...

We saw earlier how Steele's 'Who should I meet the other day but my old friend has often been used to exemplify 'incorrect' grammar. But this construction with who, rather than whom, was not uncommon. Indeed, this Ngram graph suggests that, despite the best efforts of Messrs Lowth, Murray and co, the who versions were more popular for much of the time. The peaks in the eighteenth century may well be due to its discussion in grammar books.

Here are some examples from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

The Liberall Lover, by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, in Exemplarie Novells: In Sixe Books 1640, tr. Don Diego Puede-Ser (James Mabbe)

The Parsons Wedding: A comedy, by Thomas Killigrew 1663

The Diary of Samuel Pepys - entry for March 23-25 1663

The Comical History of Don Quixote: As it was Acted at the Queen's Theatre, by Thomas D'Urfey 1694

A true and impartial collection of pieces, in prose and verse [from] the Westminster Election, published by W.Owen, 1749

Cecilia, or, Memoirs of an heiress, Fanny Burney 1784

loading...

Somebody wrote to WordReference forums with a 'question taken from an exam', where you have to fill the gap with one of the options given:

"She ____they travelled by bus."

would sooner

had rather

had sooner

I don't know whether it...

The preposition that most commonly follows 'different', on both sides of the Atlantic, is 'from' - 'She's very different from her sister'. In North America, however, some people also say 'different than', and...

The standard TEFL model - twelve tenses (or forms)

In EFL and ESL, we usually talk of twelve tenses or forms, each being a combination of a time and an aspect. Although few EFl / ESL writers would talk of a twelve tense system, that's what...

I'm tempted to say almost never, but I'll try to be a bit more objective.

Basic answer - in spoken and informal English, most native speakers use whom very rarely. This is because for most of us whom sounds excessively formal and rather old...

There’s a scene in the film Bhaji on the Beach, where three British-Indian women go to the airport to meet their Indian cousin who has just arrived from Mumbai (Bombay). As they come to greet her, she says: ‘My God, you’re all wearing saris. No...